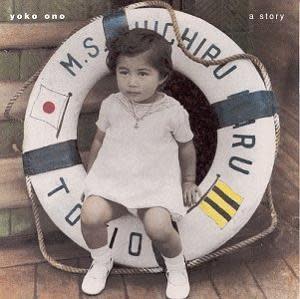

The Rock’s Backpages Flashback: In Defense of Yoko Ono in 1974

AUTHOR'S NOTE: Tidying through my papers some days ago I found, at last, an interview I did with Yoko Ono at home in New York in 1974. She was/is an idol of mine —to me, an art student in the Sixties, she was more significant and famous than the Beatles. It shocked me when she was turned into a hate figure. At the height of the anti-Yoko zeitgeist I though that if I could interview her I could tell her side of the story. Cosmopolitan, where my writing was often published, seemed the ideal place. Yoko was superb — over an evening she answered my probing questions with care and incredible candor. Unusually, because I admired her so much and because she'd been so unguarded, I sent her the interview to ensure she would not regret what she had said when she read it in cold print. Yoko rang me to say that she and John — to whom she'd introduced me when he returned home from the studio — were very happy with the text. The editor of Cosmopolitan wanted me to be more critical of Yoko, especially regarding the "fact" that Yoko "had deserted her daughter". I refused to add this into the interview, not least because I had never been asked to make such a comment about any of the divorced men I interviewed. My Yoko interview didn't run in Cosmopolitan and I put it aside. I was gutted to have let Yoko down. Finding the interview and reading it again after 38 years — well, Yoko's honesty as an artist and as a woman is as fascinating as it is moving and astonishing——Caroline Coon

*

April 1974. It is sunset. New York skyscrapers turn into futuristic Walt Disney castles flashing gold, mauve and pink as they spear into the smoky pall that hangs over the city. Two cops were gunned down last week. The survivors are mean and jumpy. In their black-blue uniforms they are easy targets for the Black Liberation Army who have vowed to wipe them out. They hang around in gangs like street kids, truncheons, pistols and Hell knows what strapped to polished leather belts slung around their hips.

Anything can happen on the streets of New York. That's why I'm not blasting down town on the subway. I'm on my way to meet Yoko Ono and I want to get to her in one piece. I hail a Yellow Cab. It crashes south along 9th Avenue lurching off pits in the tarmac and down on its axle — wham, wham, wham!

*

"The war is over in Vietnam," Yoko says, "but that's not the end of it." We are drinking red wine. But it isn't to celebrate the first day of the end of the war. Yoko is dressed in black. "There's war in Ireland and all sorts, but hopefully any war that ended will stay ended" she says with quiet sincerity.

I look at her closely, struck by an aspect of this woman who, regardless of thousands of words written about her, has remained obscured. I am rocked a little with anger, too, at those who have polluted my mind with misinformation about her. Yoko is dismissed as if she was a circus act, a clown fooling around in the arena of Concern for Humanity. Yoko Ono? Giggle, giggle. Peace? Ha, Ha, Ha! Damn, I think, is it just envy that has made people so biased? Old Nixon is getting himself nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize, and we were singing John and Yoko's 'Give Peace a Chance' years ago! Unbelievably, I cannot see a line in Yoko Ono's smooth, flawless face that might indicate the stress involved in her perpetual struggle against prejudice. Ever since she has been associated with John Lennon she's been able to put money where her mouth is. And yet most people joke about her allegiance to humanity as if she were playing some exotic game, as if she didn't really care at all.

After a recent charity concert in Madison Square Garden, Yoko and John got thousands of offers to do the same kind of thing. Everyone who needs help for all the good causes in the world writes to her for money. And they get it just as often. Women from the Feminist Movement had just been to see her because they felt she could help them. And they said: "It's so great that you still take an interest in our problems - when you're above it all." Yoko looked askance and could only say "Well..." and "Um.... you'd be surprised!"

Yoko likes to get as much money as possible from Apple, but when that doesn't work, and it often doesn't, she gives away her own: "I feel that most of the people who need money need it urgently, but whatever we are doing is just a drop in the huge ocean. Sometimes I feel that perhaps it doesn't help at all, and that as we get so criticized we might as well forget it and go to the countryside and relax a little!"

Yoko and John haven't gone yet. Yoko is managing to ignore the badmouthing and bad vibes and just get on with it. But it's been HEAVY. One butch upstanding and righteous lady of letters wrote in a glossy the other day: "Cynthia and Jane please come back. Anything which makes Yoko and Linda un-persons." It frightened Yoko, who thought it was worse than being told to drop-dead.

"You can say 'drop-dead' to your husband when you're kidding about, it's a bit cute. But 'un-persons'... And I think — why would anybody want to be nasty to me if I wasn't nasty to them. Why? And then I realize I probably did something to them without realizing it. I was a threat to them because the image of the Beatles was so big and secure, and they feel I was responsible for breaking them up. But if they learned the other side of it..."

Yoko's side to the story hasn't been heard. Yoko's background was very different to John's. His, penniless and working class. Hers, financially secure in bourgeois comfort. There the dissimilarity ends.

"In John's case," Yoko tells me, "his father went to America to earn some money and his mother was probably bored to death or something. Because she didn't have much money John was left with an Aunty — his situation was understood, and it's a big scene and out in the open. In my case, I'd never seen my father before I was three. I was born when he was abroad. He was a banker and traveled all the time. My parents were separated for two or three years, but in that kind of society everything's done subtly, there's a front. There were flowers sent to my mother probably via his secretary, and she never knew. And for birthdays there were expensive presents. She can say 'this is from my husband' to her friends, and it looks as if everything is going well. If my teacher would ask me where my parents were, I'd say, 'My mother's in Europe and my father's in America.' And they'd think it's natural they should travel. I was often on my own with nannies and maids, but it's never questioned because it's done in a place that you can't even reach. It's all done properly. But all the same, you're not very happy, especially since you don't even get the sympathy from relatives for being abandoned."

Yoko reddens slightly. And then she says that she went through guilt complexes from wishing her mother or father were dead so that she might get better parents to take care of her.

"Even when my father was in Tokyo he wasn't at home much," she says. "Finally I phoned the bank to make an appointment to see him." Another brief meeting with her father sticks vividly in Yoko's mind.

"He was going somewhere and we were all at the airport to see him off. About twenty people. And my father was like a politician. He just shook his hands with everybody down the line with a half smile that you put on when you shake hands. I was at the end of the line and he did the same to me — stretched out his hand and said, 'Thank you very much for coming,' with that same smile. And I was crying, but my mother thought I was rather silly."

Her father is an invalid now. He had a stroke, half of his body is paralyzed and he speaks with difficulty. When Yoko is on the phone to her mother, she's urged to speak to him. It's a very strained experience... "I've never really had much conversation with him. It was a very special thing to be able to talk to him. Say he was at home one Sunday afternoon, relaxing on the sofa with his pipe. I'd have to think — should I go in — perhaps I shouldn't - and then I'd go in and sit in a corner pretending I'm just looking through a magazine, and he would ask how school was or what sort of book I was reading. It was all very polite; you never showed your emotions. The conversation was always distant, but I cherished it. I didn't even show I was cherishing it. Everything he said was a golden word because I heard it so rarely."

Yoko thought her father was brilliant and she respected him. On the other hand she saw more of her mother, and it is she who Yoko criticizes and holds responsible for her mixed-up childhood. "My mother wanted to be a painter, but she always says she gave it up for my father. I don't know why though, because she had all the money and the time."

There is a deep admiration in Yoko's voice for the man who sent her to the right schools, liked her reading Das Kapital, listening to Beethoven and, from his sovereign distance, encouraged her to become an Educated Woman. However, neither of her parents had any clear idea who they wanted their daughter to be, nor were they able to let her develop her own sense of self. They wanted Yoko to be educated, it was fashionable, but they didn't really want her to put the education to use. The whole atmosphere was ambiguous.

Yoko continues: "My mother was always saying, 'There's no difference between men and women.' She would say, 'In fact, if anything, women are a bit more intelligent'". Yoko couldn't help feeling that she was being brought up as a boy. Her mother told her daughter that her marriage was a drag, that children were a drag, and that she should never do any of those things.

"I wasn't a boy, but my mother thought — this will do. She always said, 'You could be a diplomat or anything. You could be the Prime Minister of Japan.'" But when Yoko was eighteen it was a different story. "Well, Yoko," Mrs Ono said, "you're too opinionated, you show your intelligence too much and that's not going to work because nobody will want to marry you."

Yoko continues: "It was bad enough knowing I wasn't a boy, and now I was in trouble for not getting myself married off easily! I was humiliated, too, because the men my mother introduced to me were obviously not interested in my personality. They were after my properness and pedigree. My uncles shot photos of my cousins and sent them round with little notes saying, 'Well, she's of eligible age now, if you know of anyone...' There was this picture an uncle was sending round of my beautiful cousin in a swimming costume! He thought it was very modern, but I couldn't understand it. With all their education, and he does that!"

A man who "owned half of Japan" became Yoko's most ardent suitor. Mrs. Ono was thrilled. She cajoled and tempted Yoko by saying "Well, look, it's almost the same as being Prime Minister, if you're married to someone who's that powerful!"

Yoko is sitting with her elbows on the polished surface of a worktable in her open plan living-room-cum-kitchen. She hardly moves. But as she talks about a time of childhood strife far removed from her present life I feel her calm demeanor is deceptive. Yoko's very articulate external composure seems more like stillness after an explosion than inner peace.

"I think my parents were confused and that confusion reflected on me", she says with gentle understatement, and a kittenish grin on her face. It's Yoko's ironic sense of humor that has come to her rescue again and again.

Her father was an accomplished musician and from the age of five he insisted that Yoko lean to play the piano. "I was never good at it, you know. If I was at the piano he would come and say 'don't make a noise — not when I'm around'".

Yoko took up a more sociable creative activity, and began writing in a style that was not poetry or prose. Unfortunately for her, the teenage Francoise Sagan had just published Bonjour Tristesse. "Alright," said Mr. Ono, "you have another year. If you write something before that you will be famous, but after that - it's no good."

Yoko left home when she was 15. She became a bi-lingual typist in Tokyo. She made various attempts to become a singer or an actress and, eventually, left Japan for America. She studied for a B.A. in Musical Composition at Sarah Lawrence College in New York. By 1966, she was living and working in Greenwich Village, in the thick of the New York art avant-garde.

"The whole thing" she says, "was geared to the 'homosexual mafia', and women in art were only known for being 'lays'. 'Oh, that girl' they would say, 'she's been with so-and-so, and with so-and-so. She's been around.' Though men sleep around just as much, they never get that! They are not going to be known as so-and-so's boyfriend."

It wasn't much fun for Yoko. The male artists were getting all the recognition. But she was by then committed to her work and she carried on.

"In New York, the male group was trying to leave me out," she explains. "But when they did that, instead of sitting at home I'd do things alone. If I wasn't invited to a group concert or show, then I'd have to do my own. And the more you give a solo event the more you become an independent name. And my name," adds Yoko Ono with a sneaky smile, "is simple and easy to remember!"

Then she made a breakthrough into her own art language. An image from a Japanese cowboy film had montaged in Yoko's memory over a girl scrubbing the floor of her parents' house, her bottom in the air. The image was shown at an Underground film festival.

"The other films they watched with an arty attitude" says Yoko "but this film — everybody began laughing, and their reaction impressed me."

Yoko made a longer version of this film when she came to London in 1966. She called it Bottoms. For weeks all London was talking about Yoko Ono's Bottom auditions. With some art student colleagues I went along but when we got there a notice on the studio door said "Casting Over". Everyone went to the film premier! We sat in astonishment as all these bottoms, fascinating bottom after bottom, fat ones, thin ones, filled the screen with a kind of silent crack-dialogue, each bottom as indicative of it's owners personality as their faces. The film wasn't likely to put Playboy bum fetishists into a trance, but it's stark reality certainly changed my attitude to what Yoko called "the most mistreated part of your body."

Yoko made her hit underground film on a minute budget and it established her way of working. "I really feel", she says "that if I can make a film cheaply, it's like a proof that I have a very good idea. Like, let's use our own home to do this. I just keep cutting costs. I feel almost guilty to use a lot of money to make films or whatever. Because, when people ask us for money, and they write to us constantly, I feel I will have more. John might say, 'how about hiring a helicopter?' And I'll say, 'Oh, it's too costly.' But we will get it anyway, and the shots will work beautifully. But I'd never think of that kind of large-scale idea. I cut myself off from that kind of imagination, whereas John is more free about these things."

John made a film called Apotheosis which Yoko wishes she had made herself. "He had a camera going up and up from the ground into clouds and then out of them into the blue. And then the camera turns and faces into the sun. It's a beautiful idea. John says it comes from my idea 'Up Your Legs Forever' which is to film going up many people's legs. But of course his idea cost much more, because you have to hire a balloon. To tell you the truth, it's a better film than 'Up your Legs Forever'. But I'm learning!"

Although Yoko still makes films she has stopped exhibiting pictures, mainly because her work is subtle and low-key. The last show she did was in the Syracuse Museum of Art. The crowd was there mainly, Yoko thinks, because they thought there was a chance to see Ringo, George and Paul.

"The whole atmosphere", she says, "was so festive and noisy that anybody who was seriously interested in my work would have had a hard time to find it even. I started to feel guilty that I wasn't presenting Ringo, George and Paul. I felt discouraged from doing anything like that again. It just didn't work."

During her early years in New York, Yoko had cultivated her intelligence for survival. She freed herself from the bonds of traditional female concerns. She had a strong pride in herself as an individual in her own right. She did not live in someone else's home or rely on someone else to define how she should behave to please them. She worked very hard trying to perfect her own creative ideas, nor did she and rely on a man to provide for her. In fact, she says, she was phobic about connecting her name with any man, especially someone who was more well known than she was. He would, she was sure, swamp her identity.

"And then?" I ask.

"And then I met John, and ... What did I do? Something happened that just made me forget that old rule!" When Yoko finished her Bottoms movie, she opened her first solo show in London, at the Indica Gallery. The summer of 'All You Need Is Love' was imminent, and a sense of euphoric endeavor mingled with the scent of incense in the air.

The Beatles were at the crest of their wave and couldn't go anywhere without getting mobbed. The last thing Yoko could imagine was that one of them would turn up at her exhibition in Holborn. But John had been told by John Dunbar, Marianne Faithfull's husband, that there was to be a happening there.

"John thought he was going to see some erotic show with a girl getting into a bag," says Yoko. "But it wasn't like that. He came up to me and asked 'what's the event?' And I said, 'This is the event!' And I showed him a card with the word BREATH. And he went — 'sniff, sniff, like this?' And I thought he was rather sweet. And that's how it all started."

It crossed Yoko's mind that if she wasn't so preoccupied with her exhibition she would have an affair with him. But she put the idea out of her mind.

"I was getting cynical and weary of affairs and getting scared thinking that men were evil, but a necessary evil. And then again, somehow I didn't find Englishmen attractive. I'm sorry to say that, but somehow they weren't sexy. I wasn't attracted to the ritual of being proper. The thing I objected to most in the Japanese men whom my mother introduced me to was the thought that if they knew what I was like they'd never like me. I got that feeling about it all in England, too. I felt that they naturally assumed I was a nice quiet Japanese girl."

She felt that many people in the West were intrigued by "Eastern Culture" and that men wanted to have an affair with a "Cultured Japanese girl" to make life easy. Here was a real geisha girl! "I felt it was almost the same as the myth of white men with black girls — which is supposed to be very potent. And it gave me goose pimples. By the time I met John in Indica I was telling myself I was too busy to think about men. I was so cynical that when I saw John and noticed how nice he looked, I thought, 'Oh, there it is.' But I wasn't going to pursue it."

Meanwhile, John had found a ladder. He was climbing it to have a closer look at one of Yoko's ceiling paintings. "I had this magnifying glass hanging from the ceiling, and you looked through it to a tiny word in the centre of the canvas and it said 'YES'. John told me later that seeing that word decided his mind about me. He said that if the painting had said 'NO' he would have thought it was just another bit of avant-garde cynicism, and he would have wanted to forget all about it. But it said 'YES' and that made him feel good."

Feel good! John flipped! It still gives Yoko a warm feeling to remember how isolated she felt, how isolated he must have been, and how they could meet and instantly be able to communicate with one another. She suddenly had some company in her life. She would have shied away, though, if John had only impressed her as a rich, successful guy.

"We hit it off in a strange sort of way," Yoko says. "And I forgot everything. I forgot everything. Probably I was too lonely for words and too grateful to meet somebody who I didn't have to feel lonely with."

Yoko pauses. She sips the red wine. "There are moments," she continues, "when I regret it and think, why did I forget? Why did I forget the rules? All the shit I'm taking now, I just know it is the result of forgetting them! It's like one of those things... say you're crazy about someone and you get married and suddenly you realize that the mother-in-law is sitting there all the time, and you had forgotten that there was a mother-in-law. In my case, when I woke up I found the whole world was one big mother-in-law!"

© Caroline Coon, 1974

Read the rest of this remarkable interview here. Over 20,000 articles by the greatest writers from the finest rock publications of the last 50 years at Rock's Backpages.