Y! Big Story: How the media should cover mass shootings, and why it can't

The ghastly theatricality of the July 20 shooting in an Aurora, Colorado, movie theater guaranteed nonstop media attention, amplified by social media.

What wasn't guaranteed, yet inevitable, would be the dizzy scramble to name the offender, count the bodies, release unconfirmed details, speculate on madness -- and then criticize the reactionary reporting.

Analysts from the Atlantic to Fox News have questioned the journalistic impartiality. The embarrassing gaffes over identifying the correct James Holmes alone proved how the swarm of reporting in a 24-7 environment trumped accuracy.

[Related: Yahoo's complete coverage of the Colorado shooting]

The July 30 hearing, in which Holmes was charged with 142 counts of murder, was closed to the press. As news organizations prepare to argue at an August 9 hearing to have the judge unseal the case docket, a deeper concern persists: Does sensationalist coverage encourage copycats? In the sworn duty to provide the who, what, where, and when, many journalists will be asking how -- how much publicity should be afforded to a suspected killer in a case that has already become one of the year's most closely followed stories. That leads to another corollary: Can media habits change until Americans challenge their own complicity?

The calculus of crime: infamy

The coverage debate -- conducted in discussion boards, blogs, and media stories -- have ranged from focusing exclusively on victims to advocating a blackout on the suspect's name. Jordan Ghawi, who tweeted that his sister had died at the theater, returned to Twitter to ask that people join the president to refrain from "speaking the shooter's name or posting images." The impulse is to deny the alleged suspect notoriety and discourage "the next would-be spree killer."

There's a history of criminals declaring to have been inspired by violent acts, from Adolf Hitler's genocidal actions to the rampage shooting at Columbine High School. Kelly McBride, senior faculty for ethics at Poynter, points out to Yahoo!, "There's no hard science that suggests the way the media covers an event leads to copycats." The only contagion effect that has been documented by studies is copycat suicide. In such a case, the recommended media guidelines include avoiding a vivid description of the act or attributing the act to a single failure, such as a breakup or a college rejection. Those triggers "may contribute to suicide," McBride says, but the suicide happened because the person was mentally ill, not because he or she failed a test.

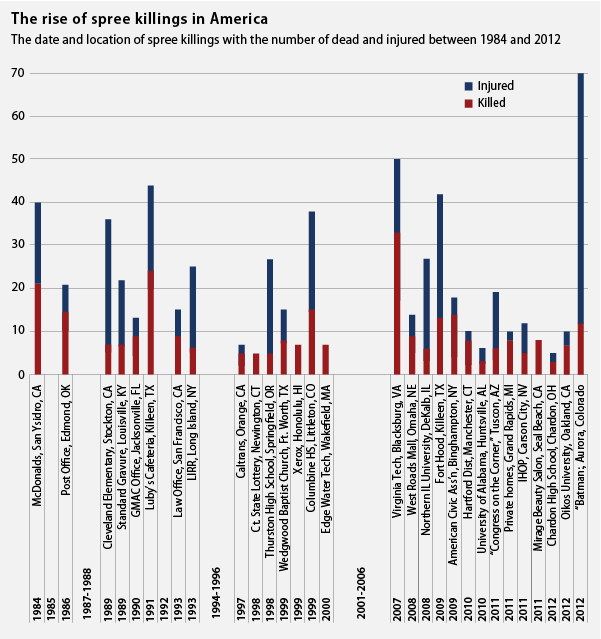

Correlation of copycat murders may be harder to come by because such killings -- serial or spree -- are mercifully rare, accounting for less than 1% of all murders. But criminal behavioralists do see infamy as a motive for a certain type of offender. Forensic psychiatrist Dr. Park Dietz, who studies mass murderers, tells Yahoo! that some angry desperate offenders will review a menu of crimes that achieve their goals. "One of the considerations in that calculus [is], what will achieve the greatest publicity," he explains. A suicidal depressive would consider mass murder and assassination; those who want to survive their crimes contemplate serial murder, arson, product tampering, and bombings.

[Related: Mass murder and mental illness]

Crime assessment expert Richard Walters classifies killers who carry out high-profile crimes among "power aggressives." One of the founders of the Vidocq Society, a nonprofit that solves cold cases and is the subject of the New York Times bestseller "The Murder Room," Walter explains to Yahoo! that the Colorado theater shooter's style of attack -- the gas mask, the costume, the setting, the damage -- was about power control. Unlike anger-excitation or sadistic killers, power-aggressive killers create a "drama bigger and better than what they should have" to compensate for failings in their personal lives, he says. "They kidnap other people's power for their own."

Duty versus sensationalism

The journalist's duty to cover what's happening without restriction is paramount. In a frantic and competitive environment, though, sensationalism can kick in, and these days, the accelerated speed of reporting in the downsized profession can cloud big-picture thinking.

While some have called for a voluntary code of ethics geared to covering mass tragedies (the Society of Professional Journalists has a general code), there's already a well-established understanding on what to do when such news breaks. Al Tompkins, senior faculty of broadcast and online at Poynter, posted sound tips immediately after the Colorado theater shootings. While he thinks a media blackout on a suspect is a bad idea, Tompkins agrees that reporters should avoid "hyperventilating terms" that describe terrified victims frozen with fear. Also, they should avoid the word "terror" in a headline. "I would minimize my use of adjectives that give power to the bad guys," Tompkins says.

[Related: Colorado families ask media to stop using shooter's name]

"Our job [as journalists] isn't to prevent or punish or any of those things. Our job is to report," Tompkins tells Yahoo!. There must be balance: Reporting the "nitty-gritty details" of how a tragedy unfolded can come across as a tutorial, he says, but it also outlines an evildoer's mindset and highlights the dangers that first responders face. For every example of overheated coverage, there is the opposite coming from seasoned newsrooms in places like Denver, Minneapolis, and Dallas, which exemplify aggressive yet respectful reporting.

The Poynter tips echoes advice that Dietz has long given to news organizations in covering mass killings: Tone down emotion and report the facts.

"I see no problem with factual information, so people who seek to understand it can read about it," Dietz says, but the "incomplete, instantaneous, often incorrect scramble for biographic material does more harm than good." It's also harmful to heighten an already highly emotional incident. "There's no need to add hysteria to the voice of the announcer or commentator or other journalists," he says. "There's no need to add sounds of commotion like sirens or wailings [in broadcast]. There's no need to stick microphones in the face of victims and those who have lost loved ones."

Vengeance and distancing

To single out the media would be a knee-jerk reaction -- as would blaming a killer's actions on a foreclosure notice, a college rejection letter, a movie, the lack of security at a theater, lax gun-control laws, or even mental illness. Journalists have an often thankless obligation to look at the worst of what society does while still upholding its core beliefs.

[Related: Expressing support for the victims through art]

Naming the offender, for instance, isn't just part of a transparent justice system; it stems from a desire for public vengeance, a holdover from the days of public hangings and stadium executions. "This is a country with a history of citizen vigilantism," Dietz says. "This is no more than speculation, but aggressive media coverage serves as a bit of a substitute for the blood lust of the past."

A media stereotype -- reinforced in detective novels and sappy movies -- depicts the killer as a loner, an outsider, someone beyond society's margins. In truth, the FBI points out that spree and serial killers "hide in plain sight" among ordinary families, living in the suburbs, working decent-paying jobs, leading Boy Scouts, or attending church. The rush to demonize makes for compelling storytelling, and it also creates a comforting distance between the killer and society. Many Americans couldn't fathom Norway's remarkably restrained response to extremist Anders Behring Breivik, which included a criminologist's declaration that the accused mass murderer was "one of us."

(CREDIT: Center for American Progress)

But why glorify a killer, beyond a deep-seated storytelling tradition of mythical monsters fighting great gods? In some ways, not only does an extraordinary villain allow us to create extraordinary heroes, but, at some level, it also absolves us ordinary folks for missing a demon in our midst.

Mutual responsibility

Yet these impulses can play into the villain-victim scenario, in which murderers become "bigger in their britches than they really are," Walters says. Even when captured, they persist in their power play by "creating a sense of mystery," from spouting a manifesto to being unresponsive. Excusing behavior with pop-psychology profiling about mental illness or other so-called triggers diminishes the killer's responsibility. "Know who the victim is and who the victim is not," Walter says.

So how can media report on the facts without creating a celebrity out of a killer or glorifying his actions? Some recommendations: Name him but shame him. Don't lead with a body count. Resist a soundtrack of hysteria and chaos. Wait for facts. Uncover his background, but don't make excuses. Avoid letting interest groups hijack a crime to push a political agenda, no matter how noble. Recognize the tragedy as a case study for societal failure, but do not create a climate of blame.

Criminologists don't hesitate to use terms like "loser," "fraud," "pretender," or "failure" in describing a mass murderer. While objective reporting would likely stay away from such language, the press could depict the behavior as contemptible rather than create a charismatic figure.

The responsibility doesn't just lie with journalists, especially in this age of social media: Audiences have an obligation to keep things in perspective and to protect themselves. Just as outlets shouldn't blanket coverage with images of the suspect and crime, consumers should know when to look away. "What we see on the news is the aberration of life," Tompkins says. "It's how you focus your lens."